Elias Teklu, a journalist and writer who became the first victim of the Ethiopian government in the 1950s.

Elias Teklu, a journalist and writer who became the first victim of the Ethiopian government in the 1950s.

This section will look briefly the revival of Eritrean nationalism in the early 1950s. Its intention is to provide background information on the early resistance to Ethiopian interference in Eritrean affairs in the 1950s.

After the UN General Assembly adopted Resoultion390 (V) to federate Eritrea with Ethiopia on 2 December 1950, Emperor Haile Selassie signed the Eritrean-Ethiopian Federation Act on September 11, 1952, and Eritrea formally joined the federation with Ethiopia on September 15, 1952.

Wago (2017) states that the legal basis of federation was the UN Resolution of December 1950 later adopted in its entirety by both Ethiopia and Eritrea as the “Federal Act.”3

However, the Federal Constitutional Law which had been ratified on July, 10 1952, did not last long. Soon after the establishment of the Federation on September 30, 1952 the Ethiopian government started to breach the “Federal Act”, when Proclamation Number 130 was issued by Emperor Haile Selassie declaring the federal Ethiopian court to be the territory's final court of appeal.

According Tekie the Proclamation was designed to undermine the independence of the judicial system in Eritrea. Article 4 of the Proclamation stated that cases decided by the Eritrean Supreme Court could be appealed to the Federal High court, although the Federal Acts and the Eritrean constitution had explicitly stated that in Eritrea the Supreme Court was the court of last resort. This was in violation of Articles 85 and 90 of the Eritrean Constitution which was approved by the Assembly on July 10, 1952. As a reaction former- supporters of the federation with Ethiopia had started questioning its workability.

Furthermore, in 1953 the Empire tightened its control by passing a law that required all males in urban areas to carry identity card at all times. By May 1953, the political situation in Eritrea had deteriorated so much that the British Consul General wrote to the British ambassador in Addis Ababa:

“The actions of the Ethiopians over the past two or three months have become increasingly suspect to anyone such as myself living in the midst of the administrative chaos in this territory. The great difficulty is to access to what extent the present situation is due either to deliberate Ethiopan machinations or Ethiopian ignorance and inefficiency. Undoubtedly the situation has deteriorated very rapidly over the past eight or ten weeks.”

As a consequences of the Federal Act violation by the Emperor, the one-time Unionist turned Federalist, Omar Kadi said that now one party is acting and the other party will have to accept the other's decision before even being born. This gives the impression of an annexation under the cloak of Federation ( Killion p39). Sheikh Radai another unionist told the consul-general: The Eritreans now realize that the Federation arrangement had been a bad one from their point of view (Killion p 54). This shows that the Emperor immediately betrayed the Unionist Party and their leaders; the Orthodox Church, and some semi-feudal Christian and Muslim population, who were in favor of the union in the 1940s (Cbaac, 2008).

By September 1953, an opposition movement was beginning to emerge ( Negash, 1997:85). Bereketeab (2000:176) also states that by 1953 “the more fanatic of the young Unionists, formerly of a ‘union or die’ attitude, have now changed their cry to ‘Federation or die,’ this was reported by British Police Commissioner of Eritrea, Colonel Cracknell.

In 1953 three youth organizations were founded, the first one commonly called simply Shabab which was the Moslem Youth League, and its leader was Imam Musa Adem, who had already been arrested for anti-government actions in 1954 along with Hajji Suleiman Ahmed. (Killion 1997:51]

The second one called Partite Giovanile Federalists Eritrea (The Young Federalists) held their first organizational meeting on Dec.26, 1953. According to Killion (1997:50). The Young Federalists had about 60-80 members and their first leaders was Tesfai Redda from Dekemhare, who was repeatedly imprisoned and tortured.

Tesfai Redda leader of the Young Federalists

The third youth organization called the Eritrean Youth Peace Council. According to Berketeab (2000:169) an organization called the Eritrean Youth Peace Council emerged, which was an amalgamation of the Youth wing of the Moslem League and the Unionist Party. Radical opposition to the incorporation of Eritrea into Ethiopia had begun in 1958 with the founding of the Eritrean Liberation Movement (ELM)

Both organizations were composed primarily of young men, representing the new and much more militantly anti-Ethiopian nationalists, a generation of Eritreans who came of age after the demise of European colonial rule (Killion 1997:51).

Furthermore according Killion, by 1958 the Young Federalist movement was part of a widespread "Federalist-Independence movement" noted by the US Consulate in Asmara, and its ideology had gone beyond the idea of simply preserving Eritrean autonomy to seeing Federation as a "stepping stone" towards independence.

All the above three youth organizations and the Trade Union took an active role in the resistance against the violations of the Federal Constitution between 1952 and1958. For example in January 1954, the Eritrean dock workers in Massawa and Assab staged strikes opposing the Imperial government of Ethiopia’s control of large scale economic infrastructure facilities of Eritrea such as transport and communication(shabait Administrator, 2012)

In 1956 and 1957 there were also major demonstrations organized by students to protest against all forms of human rights violations and the imposition of Amharic as the school's language of instruction It was sad that both the dock workers’ strike and students demonstration were brutally suppressed. Relevant link History of young Eritrean resistance in the 1950s and 1960s

Background information

Semunawi Gazetta, the weekly organ of the British Military Administration (BMA) of Eritrea, was the first Eritrean newspapers, its editor was Major Mumfort, assisted by two sub-editors, Mr Woldeab Wolde Mariam and Dr. Edward Ullendorg.

In 1942, Ato Woldeab Woldemariam, an educator, journalist and a prolific writer was appointed by the British Administration to be director and editor of the Semunawi Gazetta Eritrea (Eritrean Weekly News) and he worked there until 1950.

The Eritrean Weekly News (the Semunawi Gazetta Eritra) began to feature political essays in February 1944. The first essay of this kind was written on the 14th of the same month by an anonymous writer under the title The Fate of Eritrea (ዕድልኤርትራ) (Emaha, 2015)

Immediately after its first print on August 31 1942, the Eritrean Weekly News became a big hit. All along its ten years of publication, it ran 522 issues, each with four (occasionally six) pages (Negash 1999: 115). These amount to a huge corpus, ‘a total of more than 2100 pages or some three million words’ (Ullendorff Cited in Negash1999: 115).

In 1949 a new development appeared within the political parties when seven Eritrean political parties favoring independence in the 1940s united and formed the Independence Bloc (IB) on 26 June 1949. The Independence Bloc (IB) was composed of:

Following the formation of the Bloc, Hanti Ertra (One Eritrea) newspaper was started by the Independence Block movement and Ato (Mr) Woldeab Woldemariam became the editor of Hanti Ertra (One Eritrea) in 1950. Ato Woldeab wrote a scathing article in Hanti Ertra condemning the divisive agenda (Emaha, Samuel (2015)

It is worth mentioning that Semunawi Gazetta and Hanti Ertra besides creating democratic space and promoting political engagement, the newspapers vastly improved the modern grammatical and stylistic tone of the Tigrigna language. Hundreds, if not thousands, of essays, articles, and poems of high literary value were produced. And it is in this period and through the medium of the largely political newspapers that the essay as a distinct prose composition came into its full form.(Negash 1999: 119) read more

The role of Voice of Eritrea

In the 1940s and early 1950s Eritrea’s newspapers Hanti Ertra (United Eritrea) and Dehai Eritrea (Voice of Eritrea) played an important role in the development of national consciousness.

Hanti Ertra lived only for two years and was replaced by Dehai Ertra, whose maiden issue came out on September 21, 1952. In 1952 . Hanti Eritrea ceased its publication and was succeeded by the Voice of Eritrea (Dehai Eritra) Elias Amare Gebrezgheir gave a good explanation the reason for Hanti Eitra was replaced by Voice of Eritrea (2002) according to Elias

With the Federal arrangement coming into effect, Memhir(Teacher) Wolde’ab and his colleagues in the Independence Block considered the part of their mission of that period was accomplished, and that what remained now was to see to it that the democratic rights enshrined in the Constitution were to be defended. That mission was to be carried on by the younger generation who established Dehai Ertra. This was when Ato Wolde’ab was heavily involved in the founding and running of Eritrea’s first labor union, which became the backbone of the anti-Unionist nationalist struggle [Elias Amare Gebrezgheir (2002)

The weekly Voice of Eritrea (Dehai Eritrea) became the principal channel through which actions of the Ethiopian government and their impact on Eritrea's autonomy and constitution were discussed. The paper first appeared one week after the inauguration of the Federation. In its inaugural issue of September 21, 1952 the Voice of Eritrea advised its reader that it was no longer the voice of the M.L., rather the voice of all Eritreans, a non-sectarian and non-denominational weekly open to all views.[Tekie p41 ]

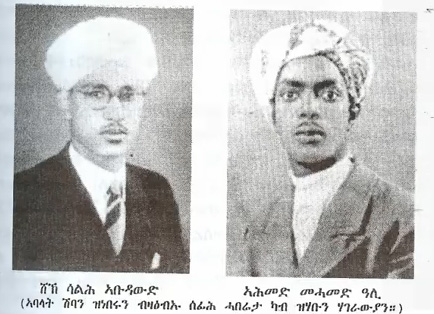

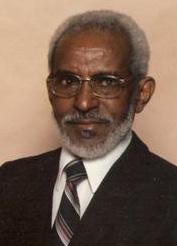

Tekie adds that since Woldeab's Hanti Ertra had ceased publication, the Voice absorbed some of the editorial that worked with Hanti Ertra. The Voice's editor was Hussien Seid Hayoti (for a while Mohammed Said Mohammed was also the editor) and it was a weekly newspaper written in Tigrinya and Arabic, with a smattering of Italian articles. Two of its brilliant writers of the early period were Elias Teklu and Siraj Abdu. [Elias Amare Gebrezgheir]

Dehai Eritrea.

Elias Teklu's article was entitled "Eritrea for Eritreans". Elias complained about the presence of Ethiopian troops in Eritrea rhetorically asking whether Eritreans are a free people as long as Ethiopian troops were stationed on Eritrean soil. He said he had nothing against Ethiopia or Ethiopians. "We want to live in peace and harmony with Ethiopia. All we are saying is that the rights Ethiopia has deprived us of should immediately be restored. If the government of Ethiopia wanted to serve the best interest of Ethiopians and Eritreans, it must respect the rights of Eritreans, and refrain from plundering Eritrean resources [Voice of Eritrean, November 22 1952 translated from Tigrinya cited byTekie p44.

Another article by Elias of the early period was titled “wshTawi naSnet iertras nabey abilu Kon iyu zguAz zelo” (Whither the internal autonomy of Eritrea?); another expose under the title of “qunqune ab hnSa mengsti iertra” (termites inside the structure of Government of Eritrea) warned against corruption of power of the Baito representatives [Read more]

One of the several articles that alarmed the Eritrean and Ethiopian governments was an article by Elias Teklu. The two-part article was entitled “Stagnation or Progress”. In this two part article Elias drew a comparison between Eritrea’s ‘constitutional government and Ethiopian’s monarchy’. The editors were warned several times, said the Secretary, but continued to publish tendentious materials “until the paper was closed”

Soon after, Dehai was illegally closed for a year. Dehai reopened on May 28,1954 by the order of Eritrea’s High Court, and it defiantly informed its readers that it will continue to fight for Eritrea’s rights against Ethiopia’s illegal encroachments on the internal affairs of Eritrea. (Elias Amare Gebrezgheir)

The Chief Executive dared the editor of the Voice of Eritrea to go to the Supreme Court for a final ruling, as stipulated in the constitution. The Eritrean Supreme Court sided with the paper, and instructed the government to allow the paper to publish.

After the government had lost in the two Eritrean courts, the Ethiopian government took over the case. Although the Eritrean constitution had made it clear that the Eritrean Supreme Court was the court of the last resort in Eritrea, the Ethiopians appealed to the Federal High Court. As expected the Ethiopian Court found the editor guilty, and ordered that the paper cease publication [Tekei p48]

On July 28, 1954, six members of the Voice of Eritrea were charged by the Federal Court for "subversive political activity endangering the integrity of the Federation and promoting its disintegration”. They were accused of working for the separation of Eritrea from Ethiopia. [Tekie p41]

Suleiman (2013) states that the Voice of Eritrea Tigrinya and Arabic editors, Elias Teclu and Mohamed Saleh Mahmud were sentenced to five and ten years prison terms respectively and the Voice of Eritrea newspaper was closed down, for publishing articles criticizing the violation of democratic rights and infringement of Eritrean autonomy. The press freedom which British Eritrea had enjoyed came to an end.

Elias Teklu who was later imprisoned for his vigorous defense of the democratic constitutional rights of Eritreans and was taken to Ethiopia were he languished in prison for five years and finally joined the rank of the early martyrs.

Dehai finally ceased its publication with its last issue # 50 published on August 6, 1954. This was when the first journalists became victims of the Ethiopian security forces, in violation of the Eritrean Constitution Article 32, which stated: “Everyone resident in Eritrea shall have the right to express his opinion through any medium whatever (press, speech, etc.) and to learn the opinions of others... The 1952 Eritrean Constitution incorporated many of the ideas of the Declaration of Universal Human Rights recognised by the UN. one of that article was Article 32.”

. The first nineteen teachers

When Eritrea was a colony of Italy there were a few school teachers who had been trained by the Swedish Evangelical Missions (SEM). For example, Ato Woldeab Woldemariam who had served in the Swedish Evangelical Mission School system of Eritrea first as a schoolteacher and then as the director at the Geza Kenisha School between 1931 and 1942.

In the early years of the British Administration apart from a few teachers like Ato Woldeab Woldemariam Tseggai Iayasul etc., who taught at the Geza Kenisha, most teachers of that period were recruited locally at the teacher training schools set up by the British Administration. The first nineteen teachers were recruited from this school in 1943. Wago (2017)

During the 1940s and afterward the Eritrean teachers did not confine themselves to professional matter but also involved themselves in politics. Thus, for example Ato Woldeab Woldemariam, who was a teacher, journalist and politician contributed great to Eritrean politics right up to the early 1950s. He and other teachers, influenced the young generation who became actively involved in politics in 1950s and during the 30 years of liberation struggle.

Ato Tseggai Iayasu

Among the first school teachers at Geza Kenisha in the early 1940s was Ato Tseggai Iayasu who became a lawyer later. Ato Tseggai Iayasu was recruited by Haraket and actively participated in the underground organization led by Haraket in the late 50s and early 1960s. During those years Ato Tseggai Iayasul was repeatedly imprisoned and tortured by the Eritrean security services.

Many will have heard about the students demonstration against the imposition of Amharic as the school's language of instruction in 1957 Regarding this demonstration, Killion (1997:53) states that in protesting against the imposition of Amharic on Eritrean schooling as the language of instruction. It replacement by Tigrigna and Arabic, at high schools, led students to organise demonstration, school boycotts and other acts of resistance in protest.

Unfortunately there has been little acknowledgement of contribution of Eritrean teacherswho protested against the imposition of Amharic as the language of instruction and encouraged, or influenced their students to protest against the imposition of Amharic, and other related issues such as unequal wages for Eritrean and Ethiopian teachers. One of those students who was influenced by his teachers in the 1950s was Ande Michael Kahassa

Ande Michael Kahassa was a student at St George and moved to Asmara to purse his secondary schooling. He explains in an interview that when he went to high school, in 1959, there was resistance to Amharic in his group. “Our favourite method was to eat dried chickpea during class. It was very noisy. We were known as the chickpea market. We were notorious. The Ethiopian teachers were also transferred to Eritrea to teach Amharic. Teachers wearing army uniforms (apparently to intimidate students) were met with open hostility.”

Ande Michael Kahassa also mentions that the Eritrean teachers at that time had a starting salary the equivalent of $20, later it became $80, whereas the starting salary of the Ethiopiaan teachers was $250, because all the revenues from the port and so on from Eritrea were going to the Ethiopian Federal Government. “So our Eritrean teachers were dressed in Khaki, the same Khaki that they wore the year through. But this teacher came in a three-piece suit and a neck tie.

In 1950s and 1960s, the contribution of Eritrean teachers to politics was not limited to their students. They also established their own professional association which enabled them to work closely with the Trade Union to protect the civic and political rights of the Eritrean people. The Teacher Association was formed in Awald School, Asmara, which renamed Adulis junior School in 1958. [ Solomon, (2017)

As a consequence of their active involvement in the 1958 three days General strike, the Asmara Teachers' Association was banned in 1958, and its leaders briefly arrested. Following this, Eritrean teacher’s started to use different methods of struggle to protect the federation.

Although the Teachers Association was closed ,the Eritrean teachers continued their participation in the civic and political right struggle through joining the underground organization Haraket and the Asmara Theatre Association ( MATA) in the 1950s and 1960s respectively . Among those teachers who joined the Asmara Theatre Association ( MATA) Memhr Asres who taught at Sant George in 1959, Memher Solomon Gebrezgabiher with his sister who taught at the elementary school involved acting in the stage as comedians and Memhir Alamin Abdeletif was Legendary Artist.

In the 1957 there was another related cultural association established which included many teachers, as well as singers and dramatists. It was called the Mah'ber Memeheyash Hagarawi Limidi ("Association for the development of National Culture" M.M.H.L). With 45 members, it staged several singing and drama productions in Mendefera and at the Cinema Impero in Asmara (attended by 3,000).

Amine Gebre Kristos, a participant and worker at the Government Printing Press, along with two other M.M.H.L. members were imprisoned and tortured for 3 month following the Asmara show. [Source from "The Eritrean Workers' Organization and early National Mobilization 1948-1958 by Tom Killion]

The Eritrean teachers of 1930s generation greatly contributed in the revival of Eritrean nationalism through the raising of national consciousness and by influencing their students’ political view in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. The involvement of Eritrean teachers was not restricted to raising national consciousness among their students, they themselves joined the fronts and contribution their professional expertise in the ELF and EPLF Education Departments. During the liberation struggle Eritrean teachers of the 1940s and 1950s generations also became the Ethiopian security forces’ victim of imprisonments, tortures and executions. To mention some of those victims:

In 1974 Dr. Petros Habtemikael a lecturer at Asmara University had been killed by strangulation with Piano wire, a trade mark of the death squade.

In 1979, twelve teachers were detained on suspicion of collaborating with the EPLF, and some of them were subsequently executed,

In 1980 a women teacher named Mebrat was executed with other 10 teachers,

Unfortunately apart from the history of Memhir Woldeab no one documented the role of Eritrean teachers in the 1950s revival of the Eritrean nationalism.

To conclude Eritrean nationalism reached a peak in 1958 when the underground unions staged a general strike in Asmara and Massawa. During the three days strike the youth organisations, teacher association, cultural association and others joined workers in massive protests against the loss of local autonomy which will be briefly discussed in the next sections.

Generally the youth organisations, teachers’ association, cultural association and trade unions all greatly contributed to the rebirth of Eritrean nationalism in the 1950s .

ehrea.org © 2004-2017. Contact: rkidane@talk21.com | ||||