Compiled and researched by Resoum Kidane 16-11-2014 [preliminary draft]

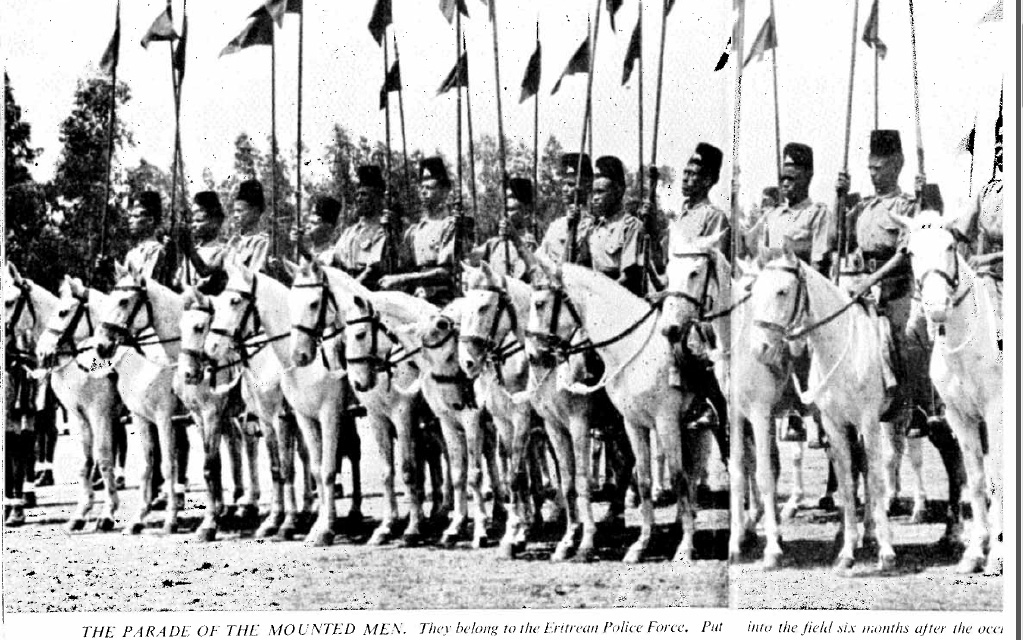

Background information on the formation of the Eritrean Police Force in 1941 excrept from the First to be Freed published London: His Majestry Stationery Office 1944.

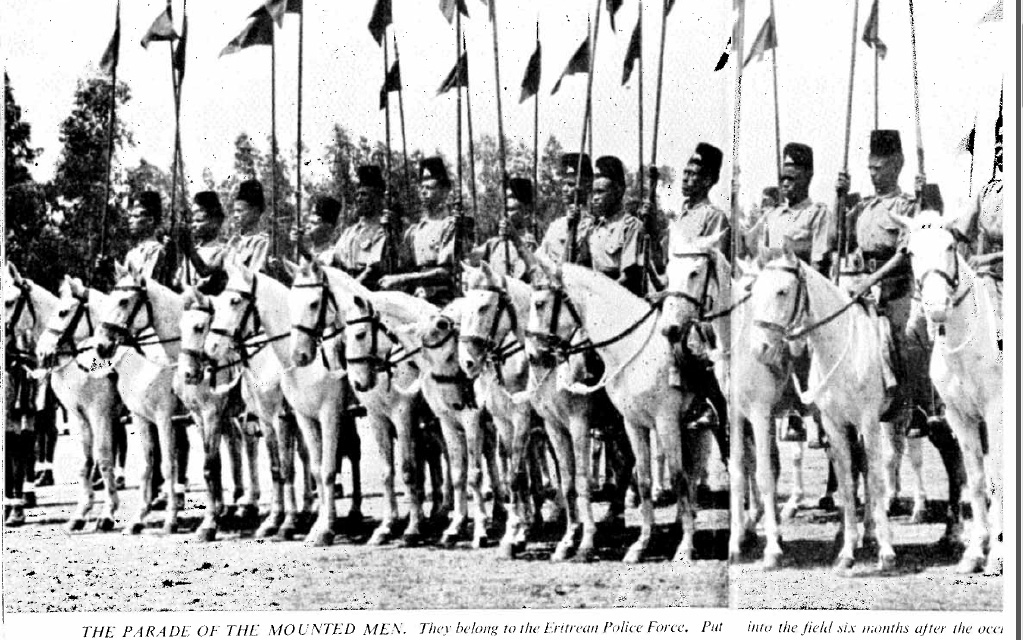

In August 1941 six months after the occupation with the arrival of an adequate number of trained officers from Southern Rhodesia the Eritrean Police Force began to take the field. It consists of 3, 000 Eritreans, under ninety -seven British officers and inspectors. It has a strong C.I.D, branch, with finger-print, record and photographic section: four armoured cars, which once belonged to the Italians: a half-squadronof some sixty mounted men; and a striking force 250 strong for repelling raids from beyond the Ethiopan frontier. There has never been any lack of volunteer recruits, who receive pay, uniforms, and three months, training, and come from a great variety of tribes. source page 25. .

Yohannes Ferdinando Drar posted this on facebook and wrote the British as colonial administratars were fair enough to teach/hire Police officers from different tribes/regions of eritrea.Which was later undermined by General Tedla Ukbit during his brief leadership as Police Chief in eritrea during the Federation.After, his mysterious assassination by ethiopian government, he was then replaced by General Zeremariam Azazi ,who is from the Meansa Tribe from the Senheit Province.Both,were trained during the British Military administration in Eritrea

Eritrean Music Interview: Eritrea Police Orchestra

A Bit of Eritrean History at Bridport, UK

Contributed Article

(Originally published in Eritrea Profile, August 11, 2002)

By Alemseged Tesfai *

The train ride from London to Bridport in Dorset was a pleasure. My envious eyes feasted on the greenery of the English countryside, attempting all the time to place the scores of fictional characters I still remember from my high school readings into the hilltops and old buildings sprawled along the way. For some reason, Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Ubervilles stood out most vividly in the habitat where she was supposed to have met her fate.

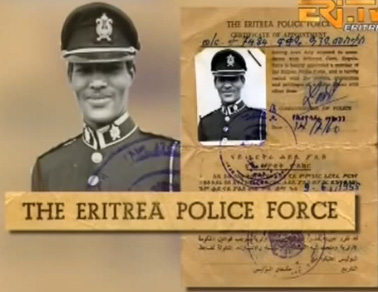

The purpose of the visit was to meet with and talk to the first Commissioner of Police of Eritrea at the start of the Federation, Colonel David P.P. Cracknell. A friend, the British writer Michela Wrong, had arranged the visit for me and the Cracknells had been kind enough to invite me over.

As I alighted at the small station that serves the Bridport area, Jeanne Cracknell had no problem spotting me from a distance and welcoming me with open arms. This was my first visit ever to an English family, but her smile, sprightliness and manifest energy put me immediately at ease.

"David is an official at our local church. They are still at a funeral. We will join him soon," she told me leading me towards her small car. "I am going to drive you some twenty miles into Bridport. We live just outside the town. I hope you don't mind a woman driver."

"Of course, I don't," I replied and soon found out that she had been modest about her driving. As we sped through a narrow and meandering slope whose wall of hedges concealed what lay beyond every curve, I could not hide my admiration at her skill and expressed it to her.

"David and I got married at a church in Gajiret in '48," she said. I smiled, amused and a little thrilled at the idea of discussing Gejeret somewhere in Dorset.

"That would probably be the San Francesco Church. Was there a statue of St. Francis at the square in Front?"

She could not remember. There was no Anglican church for the English community in Eritrea to go to. They were thus allowed to use Italian Churches throughout the country.

Bridport is a small town on the English Channel. The narrow street we passed through was a blend of old and new buildings, very clean and quiet, perhaps conservative too, and typically English. The funeral service was not yet over, so Jeanne Cracknell ventured to show me the Channel. It was a windy morning and the sea was in an angry mood. As it heaved and subsided, a couple of fierce waves crashed into the dyke allowing splashes of water to fly high over and rain upon us. We had to run back into the car and head towards the church. That was my first glimpse ever of the English Channel that I had heard so much about.

We met Colonel Cracknell inside the church, where he and the pastor welcomed me. A stout octogenarian, he must have been of considerable physical strength in his younger days. "Welcome, Alem," he said, startling me with the ease with which he had shortened my first name. I mumbled something in reply. "You must speak louder. I can't hear very well and you can call me David. You've met Jeanne. Her name is spelt the French way."

The Cracknells live on the edges of Bridport, at a place called Walditch. Their little villa sits on top of yet another slope, thus commanding a nice view below. I was enjoying the near perfection of the back garden through the window of the living room when David Cracknell poured us some wine and we started talking.

He asked me about some of his old colleagues at the Eritrean Police Force, Alem Mammo, Seyoum Kahsai, Yigzaw Berakhi, Zeremariam Azazi, Erdachew Emeshaw, etc. I told him Alem and Yigzaw are still alive, but that many of the rest had died since. He also talked about Tedla Ogbit, one of his successors as Eritrea's Police Commissioner and how promising he had been at the early stages. Cracknell's duty had been to organize the Eritrean police force and he was unsparing in his praise of the eager young men that had staffed its rank-and-file.

I opened my handbag and gave him some old Foreign Office documents that I had had photocopied at the Public Record Office in London. They contained a report, signed by him, of an interview that he had carried out with Tedla Bairu, Chief Executive of federated Eritrea from 1952 to 1955. He withdrew to the dining room, leaving me to pore over pages of documents from his own neatly preserved files. I was engrossed in one particular report detailing the surrender of Hamid Idris Awate to the Eritrean Police force led by Cracknell himself in 1952, when he came back to me, clearly immersed in his own distant past.

"I must have been brave to have said all that to Tedla Bairu himself," he said, not concealing his own satisfaction.

It was, indeed, an unusual interview where Cracknell had expressed his disappointment at the way the federal arrangement between Eritrea and Ethiopia was or was not working. He had been brutally frank in his criticism of Tedla for the latter's failure to protect Eritrea's rights and to allow the Ethiopians to intervene in Eritrean affairs at will. He had also accused the Chief Executive of, among other things, nepotism and a vindictive attitude towards his political opponents. I asked Cracknell to elaborate on all the points raised in that interview and he told me what he could remember. We both agreed, however, that Tedla Bairu had been remarkably cool and civil in his reply. We talked at length about Tedla's government and the Eritrean Police force during Cracknell's tenure, but that is material for an upcoming book.

I was in Bridport for only three to four hours. We thus had to cover a lot of ground in a hurry. He had come to Eritrea in 1941 from what were known as the Rhodesias at the time. As a one star lieutenant, he had been placed on top of a few Italian carabinieri and about 150 former Eritrean zabtia, the indigenous police troopers under Italian rule. "Were the Eritreans good students?" I asked Cracknell.

"They took to it, as one may say, like a duck to water. They enjoyed it. They were entirely loyal. I had no case at all of disloyalty. The Italians, on the other hand, were rather amusing. Coming into office in 1941, when things were going badly for the Allies in the desert, the carabinieri wouldn't even greet me. They would push you off the pavement. But a few days later, when things were going well for the Allies, Tobruk had been retaken and so on, they were leaping to their feet and saluting and bowing and scraping 'Signor Colonello' and all that." But he went on to praise Italian industriousness and the pivotal role that they had played in keeping the Eritrean economy going.

We talked about the shifta problem throughout his tenure.

"The Mossazghi Brothers were bad," he told me. "But Tekeste Haile was particularly blood thirsty."

"Were the Ethiopians behind that shifta movement?"

"There was this blessing. They crossed into Ethiopia with impunity. They weren't sought out or arrested by the Ethiopians. I did know that the Ethiopians had a hand in it. There was no doubt in my mind."

"Do you remember the Sudanese Defence Force massacre of unarmed Eritrean civilians in 1946?" I asked him.

"Yes, very well. A terrible tragedy."

"Do you know that many Eritreans from that period accuse the British of connivance in that event at least for having failed to take prompt action to stop it?"

"I'm sure they would," Cracknell responded. "The stupidity was that they should never have brought Sudanese troops into Asmara. In fact, it was understood that Sudanese troops should not be billeted in Asmara. But the politicians did that. It was a terrible day."

"Where were you when it happened?"

"I went down to the scene when I heard the shots. But a Sudanese trooper pointed his bayonet to my chest and I was there against the wall. I couldn't get to my men."

It was Eid el Fatr that day, he said, and most of the British army officers had been out playing polo or vacationing somewhere. Eventually, they did come and the Sudanese withdrew. "I can understand how the Eritreans can accuse us of complicity," he concluded. "In fact, subsequently, they asked me to give them weapons from the armory, but I refused. Can you imagine what would have happened had I done that? It would have been more massacres. The worst part of it was that many of the Sudanese soldiers were acquitted for lack of evidence linking individuals to particular crimes. Terrible yes, Eritreans would suspect connivance."

"I understand there were Jewish activists interned in Asmara. Can you tell me about them?"

"About 1947, I think. They had been accused of terrorist activities out there and they were brought over and interned in Sembel. 107 of them escaped in twos and threes, and one lot of fifteen. 106 were recaptured; only one made it to France his name was Eliahu Lankin. Another man I had difficulty in recapturing was to become eventually the Prime Minister of Israel Yishak Shamir, a little, short fellow. I knew he was trying to get to Italy on an Italian boat in Massawa. I blockaded the ship so he would not go down to it. I then arranged, secretly, a water tanker to be available for him to hide and come back to Asmara. The driver was my own policeman, you see. I ambushed the water-tanker on the outskirts of Asmara and there they were, the two of them" In other words, Cracknell had set the trap.

At last, we talked about Hamid Idris Awate, the patriot who started the Eritrean armed struggle. "He was a thorn on our side," said Cracknell, "The man lived by the sword." He gave me some examples of why he had said that.

"How did he surrender?"

"Determined to bring him in before the hand-over from British to Federal rule, I took with me the holy man from Keren (and other dignitaries). I went to Haikota and sent out spies. Awate said he would meet me at dawn the next day. He surrendered to me. But he also wanted to be protected, so I allowed him to have five rifles, provided he kept close to the police post at Guluj, which he did. In later years, I found he had become far smarter than the local police there. I have some photographs of him somewhere."

I lit up, of course, and asked if I could see them. Cracknell brought some old photo albums and after leafing through them found three photographs of Awate and his men on the day of their surrender in 1952. I had never seen those pictures before. In fact, there has been a controversy about whether the man on horseback that is identified as Awate is actually he. Well, David Cracknell put that issue to rest by recently sending me that exact picture and more from his other albums. He also surprised me with two vivid pictures of Ali Muntaz, the shifta of the early 1940's and Awate's own mentor.

At the end of our talk and after Jeanne Cracknell had fed us a delicious lunch and not, by any means, fish and chips they were both concerned that the interview may not have been worth my trip all the way to Bridport. Incidentally, as she moved in and out of the dining room, where we were, she was all the time making comments, helping her husband recollect and enriching the interview. I told them that they had helped in more ways than they would ever guess.

As I started to leave, I asked David Cracknell what his feelings were about Eritrea " I have very kind memories," he said "After all, I spent the best part of my life in Eritrea from 1941 to 1954, thirteen years apart from two in Somalia. Thirteen years between the ages of twenty-two and thirty-six, one's best years of life put into the Eritrean police force. It's my pride and joy." Then referring to the last war with Ethiopia, he said, "It was so sad to see it wounded in that way, as it was. I hope that, at last, peace is at hand."

Cracknell insisted that he see me off at the train station twenty miles away and Jeanne drove us back with the same ease and efficiency. We hugged good-bye like old friends. I am sure that most of the people in Bridport may not even have heard of Eritrea. But, as I waved the couple farewell from inside my train, I felt as if I was leaving a bit of Eritrean history in that charming house up on Walditch.

I have almost two hours of tape from the Cracknell interview. I find that the English do not speak English the way the Cracknells do not anymore.

* Alemseged Tesfai, who is currently a senior fellow researcher at the Research and Documentation Center of Eritrea, writes on the history of Eritrea and the Eritrean People's Liberation Army. He was Head of the Cultural Division of the EPLF and the Cultural Center of the Department of National Guidance in the Provisional Government of Eritrea. A writer and playwright, Alemseged has produced a collection of short stories, plays, essays and a novel about the Eritrean Liberation War. His play 'The Other War' was produced in the West Yorkshire Playhouse, Leeds, UK, in September 1997, and was recently broadcasted on air by BBC radio. His latest book of Eritrean history in Tigrinya, AYNFELALE: Eritra 1941-1950, (Hedri Publishers, Asmara, 2001) deals with early Eritrean nationalist history and politics of 1941-1950. His collection of short stories and essays (originally published in Tgirinya as "klte qnde ab dfaAt" by Hidri Publishers) has also been recently published in English by the Red Sea Press under the title "Two Weeks in the Trenches" (2002). A prolific writer, Alemseged is currently busy preparing the publication of his second volume on Eritrea's history of the Federation period.

|

Tedla Ugbit who supported the Pro-Ethiopian polices that led to Annexation, and his deputy, Goitom Gebrezghi, police Commander of Asmara, was instrumental in suppressing the 1958 General Strike. During the general strike and demonstrations of 1958 the British consul noted that the majority were Christian and that UP members were “mostly very anti-Ethiopia ( Pool, 2001:53). During the attempted coup of 1960, Mengistu Neway, leader of the coup communicated with General Tedla Uqbit requiring him to secure the borders as the military committee which he lead had decided to recognize Eritrea’s independence. But the Eritrean General rejected the offer and preferred to welcome the Emperor in Asmara, on his way from Sudan (Ali, 2007) . As a result of this, the coup was failed and the Emperor returned to the capital on December 17, 1960. |  |

|

Tedla Uqbi inspecting Eritrean police in the 1950s: Tedla Uqbit, Brigadier-General (?-1963): an ardent Unionist who persistently worked and assisted the annexation of Eritrea. Trained under the British, Tedla Uqbit became one of the most feared Eritrean personalities during the Federation years. In 1951 the British Administration sent him for study to England. In November 1954, alongside with two other police officers, dismissed by the Chief Executive on the grounds of redundancy. Tedla Uqbit resigned from his post rather than accept a transfer to a civilian position, giving his reason that his dismissal had been due to his strong support for Union. His case was taken up by the palace, and with pressure from the Federal government, in May 1955 the Chief Executive forced to appoint Tedla Uqbit as deputy Police Commissioner with the rank of Major. [Standing Left to right: Tedla Ogbit, Rezene Berhanu, Seyoum Kahsai, and Zeremariam Azazi, with trainers at a British Police training center --------------------- Source of the picture: Almeseged's latest book] Rezene Berhane became a Director General of the Department of Interior, while Seyoum Kahsay was asked to command the Finance Guards. Of course Tedla Ogbit and Zeremariam Azazi became generals and commissioners of the Eritrean Police Force. Tedla was presumed to have committed suicide, while Zeremariam Azazi succeeded Tedla and eventually became accredited as Ambassador to Ghana where hepassed away and his remains were buried inn Ghana, if memory servs me well.comment posted on facebook by Habte Teclemariam |

In September 1955 replaced the departing Police Commissioner of Eritrea, the Briton Colonel Wright, Tedla became the Police Commissioner of Eritrea. Later in his capacity as Commissioner of Police, Tedla was to be responsible, for the dismantling of the federation. During the 1956 Assembly elections he was at the forefront in harassing anti-Unionist candidates. Although free to harass, he remained accountable to the Eritrean Supreme Court, which was headed by Sir James Shearer. Tedla Uqbit was known for his ruthless suppression of actual and anticipated dissension so that by the beginning of 1960 he had managed to muffle all signs of opposition in Eritrea. The departure of Sir James Shearer in 1959 gave him absolute power and a free hand to jail anyone with impunity. In June 1962, for his unwavering service to Ethiopia, Tedla was promoted from colonel to Brigadier-General by Emperor Haile Selassie and bestowed the title of "Commander of the order of the Honor of Ethiopia."

During the abolition of the Federation he was the busiest man to make sure all Eritrean Assembly members available for the intended final vote to terminate the Federation. Surprisingly, nine months after the fall of the Federation he lost his life in confrontation with the regime he loyally served for years. ጀነራል ተድላ ዑቕቢት ከም ኣባል ማሕበር ኣንድነት መጠን ንጃንሆይ ኣገልጊልዎም እዩ። ናይ 1960 ዕልዋ መንግስቲ ኣብ ኢትዮጵያ ምስፈሸለ እሞ ኃይለ ሥላሴ ናብ ኢትዮጵያ ክምለስ እንከሎ ኣብ ኣስመራ፡ ኤርትራ እዩ ዓሪፉን ካብኡ ንኣዲስ ኣበባ ኣምሪሑ። ኣብ ኣስመራ ባዕሉ ተድላ ዑቕቢት እዩ ተቐቢልዎ። ሽዑ ዝሃቡዎ ገጸ በረከት ሽጉጥ ክሳብ ዝመውት ኣብ ኢዱ ኔራ ይበሃል። ንሱ እውን ብግዲኡ ንብዙሓት ሰባት ከም ሓላፊ ናይ ፖሊስ መጠን፡ ኣብ ኣብያተ ማእሰርቲ ዳጉኑን ኣሳቕዩን እዩ። ግንከ ኩነታት ሃገር ናበይ የምርሕ ከምዘሎ ምስተረድኦ፡ እሞ ነቶም ምስኡ ዝነበሩ ሓገዝ ምስሓተተ፡ ልክዕ ከምቲ ኣብ ላዕሊ ዝተጠቕሰ፡ “በዲልካና ኢኻ” ብምባል ናብ ሓደ ናይ ወጻኢ ሓይሊ ኣሕሊፎም ብምሃብ እቶም ክሕግዙ ዝኽእሉ ዝነበሩ ባእታታት ሱቕ ብምባል፡ ናብ በይኑ ምኻንን ንባዕሉ ከምዝጠፍእን ተጌሩ። እዚ ሰብ እዚ ግን ካብቶም ካልኦት ዝፈልዮ እንተኔሩ ብቑዕ ሓይልን፡ ስጉምቲ ናይ ምውሳድ ክእለትን፡ ወሳንነትን ዝኣመሰሉ ናይ መሪሕነት ጠባያት ዝነበሮ ውልቀ ሰብ እዩ። ደቅሰብ እንተዝሕግዝዎ ኔሮም እቲ ኩነታት ኣበይ ምበጽሐ ዝብል ሕቶ ይለዓል source Sourceትውልዲ “ኣለና”፡ ኣሎ ከይትብሎ የልቦን: የልቦን ከይትብሎ ኣሎ። 1ይ ክፋል by ኣራራት ኢዮብ on 16 November 2014 Tedla Ogbit who was active in the assembly intimidating members and interrogated ELM (Haraka) members was recruited by Tuku’e Yehadego’e .After Annexation, Tedla Ogbit, Goitom and Second in-command Zemariam-Azazi, were flown to Addis Ababa and entertained by Haile Selassie. Nonetheless, Tedla Ogbit had a change of heart following annexation and on June 11, 1963 was found shot to death in his office after he had apparently been involved in a plot to restore Eritrea’s independent status. This plot was part of the larger ELM plan to infiltrate the Eritrean police and use them to carry out an anti-Ethiopian coup d’état through the plan never materialized, many Eritrean police were sympathetic to the nationalist movement. Immediately after Tedla’s death, police headquarters was surrounded by Ethiopian troops and a number of leading Eritreans were detained. Zemarian Azazi replaces Tedls and was promoted to Brigadier-General ( Killion 1991: 341)

In protesting against the suppressiion of the 1958 General Strike in March and April 1958, eighteen prominent citizens including Omar Kadi were arrested for sending a telegram to the UN Secretary-General protesting against Ethiopian violations of UN Resolution 390A(V). Negash(2005:129) adds that in a radio interviw in Cairo Omar Kadi said that Eritrea was being ruled by a black colonial power.On the basis of the information supplied by Tedla Ogbit who was chief of police, the Federal Attorney General filed a criminal charge against Omar Kadi in the middle of March, 1958. Because of above allegation, Omar Kadi was sentenced to ten years while the others were detained for short term or released on bail (Iyob,1995: 91) Following the general strike on May 13 a repressive Labor Code was passed and the Confederation was outlawed. Since then the Ethiopian government began to suppress of basic political rights and civil liberties and it reached its peak after 1958. For example Bereketaeab (2000:173) provided additional the following examples: In 1954, a strike by dockworkers in Massawa and Assab against the introduction of a compulsory Federal Identity Card was suppressed by force, the 1958 peaceful general strike was also suppressed by force. The Voice of Eritrea newspaper was closed for publishing articles criticizing the violation of democratic rights and infringement of Eritrean autonomy with the imprisonment of the staff writers and arrest of newspaper editors. Between 1958 and 1962, the Ethiopian government never stopped violating the UN Resolution which had been ratified by the Empire on September 11, 1952. By replacing the Eritrean flag with the Ethiopian flag in 1958, the Eritrean Penal Code by the Ethiopian Penal code, by changing the name Eritrean Executive to Eritrean Administration, and the Chief Executive to Chief Administration. |

In 1957, the Ethiopian government banned trade unions, closed many Eritrean industries, dismantled Eritrean factories and moved them to the capital city of Ethiopia , Addis Ababa. As a result, the number of workers in Eritrea declined from 32,400 (27,000 Eritreans; 5,400 Italians) to 10, 350(10,000 Eritrean; 350 Italian).

The once urbanised Eritrean population, who originally came from rural areas, could not return to the countryside, because the skills which they acquired during the period of Italian colonial rule and British administration could not be applied in the rural areas. Consequently, most Eritrean skilled workers started migrating to Ethiopia to seek for work, to reunite with families, to obtain opportunities for further education and to establish businesses

Spencer (1984: 303) also states that with large numberes of Shoans came to occupy the federal offices in Asmera and Massawa, the influx of Eritreans into Addis Ababa was on large scale as gradually to dominate the Ethiopian Air Force and the Police, 40 percent of the Army officers corps, much of telecommunications and nearly 100 percent of the taxi drivers in Addis Ababa. The Eritreans soon proved themselves to be the Irish of Ethiopia.

Fig. 2: The fluctuation of Eritreans immigrating to Ethiopia between 1957 and 1998. Source: from the statement by the delegation of the State of Eritrea to the UNHRC, 4th August 1998. The origin of this source was presented in table format not in a graph.

Erlich(1983) pointed out that one factor of the considerable socio‑economic development in Ethiopia was the growing participation of Eritreans in Ethiopian national life, which was able to supply Ethiopia with the necessary manpower (1950-1960s and early 1970s). Therefore, one would assume the building of modern Ethiopia could not have succeeded without the participation of skilled workers and other intelligentsia from Eritrea. An evidence of this could be seen from the role of Eritrean workers in the formation of the Ethiopian Labour Union in 1963. According Asafa (1993:105) One of the opposition forces to Haile Selassie's regime was the labour movement. The government prevented the working class from organizing itself into a union until the early 1960s by denying it legal status. The incorporation of Eritrea into the empire in the early 1950s brought in Eritrean workers who had union experience, and the influence of the International Labour Organization necessitated the proclamation of Labour Relation DecreeNo.49 of 1962, which facilitated the formation of the Confederation of Ethiopian Labour Unions (CELU) IN 1963.

ehrea.org © 2004-2017. Contact: rkidane@talk21.com | ||||